Rudolf Hirt

God of the Waters

Artwork Brief Description

This monumental sculpture reimagines water deities beyond the Western archetype of Poseidon. Hirt’s *God of the Waters* exudes serenity rather than power, inviting contemplation. At night, an ethereal mist and illuminated figures inside the sculpture create a theatrical, otherworldly experience, reinforcing its mystical nature.

Rudolf Hirt (born October 19, 1947) is an Austrian sculptor.

Influenced by his father, who was a resistance fighter and communist, he attended the master class for sculpture and painting at the Ortwein School in Graz after completing his apprenticeship as a sculptor. He completed his studies at the Academy for Applied Arts in Vienna.

After years of traveling the world, he returned to his hometown Scheifling in 1977, where he works as a freelance sculptor.

He is married to Angelika Hirt, who is also a sculptor and with whom he has three children who are also artistically active. Together with his wife he founded the Hirt-Haus Atelier, where he organizes exhibitions, workshops and symposia.

Rudolph Hirt (Austrian b.1947) Dio Delle Acque (God of the Waters), 1992

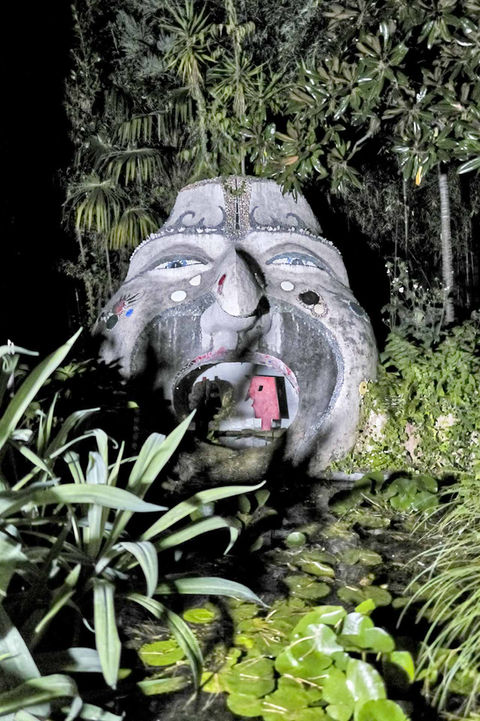

As we ascend the garden, we encounter Rudolph Hirt’s striking “Dio Delle Acque” (God of the Waters). At the base of this monumental sculpture, the god’s mouth is open, much like the mouth of a river, cascading into a pond that trickles down into a small waterfall. The oriental headdress and distinct facial features of Hirt’s deity immediately suggest a departure from Western sea gods such as Poseidon, who is often depicted as a man holding a trident, which he uses to stir the water. Unlike Poseidon, who had the power to create storms, earthquakes, floods, and even droughts, Hirt’s god evokes a sense of tranquillity and mellowness.

In fact, despite the large open mouth, the sculpture is devoid of aggression or the dominating characteristics associated with western gods. Instead, the viewer is invited into a more contemplative experience. Upon closer inspection the interior of the god’s mouth reveals an extraordinary scene; characters in profile, seemingly engaged in dialogue, as if performing on an ethereal stage.

This sculpture truly comes alive in the evening, when the inner stage cum mouth is illuminated, and gentle mist streams from within, reinforcing ideas of otherworldliness. The figures are rendered puppet-like with their minimalist forms and block colours of either red or black that remind us of this ancient art of storytelling.

Looking directly at the puppets, it is clear to see that the face of the god is, in fact, wearing a mask. This realisation underscores the sculpture’s central metaphor, that appearance can be deceiving. In contrast to the straightforward depictions of a “God of the Waters” as found in the Western art canon, this sculpture invites the viewer to ponder the deeper, more enigmatic nature of divine power as it is conceived in various cultural contexts. The use of symbols and motifs from both Eastern and Western cultures in perfect harmony adds to the challenge to our preconceived misconceptions of what it means to be a “god” and what forces they represent.